When Famine Devastated West Cork

The Famine sparked

off a decline in the Irish population which lasted half a century. It

concentrated within a short period many changes in Ireland's social and economic

life which would have occurred but not so suddenly. One of the major disasters

of the nineteenth century, the Famine marked a great divide in modern Irish

History and, through the impact of emigration, its effects spread far beyond

Irish shores. Cork and especially West Cork were among the worst hit areas.

It is hard to believe that the invasion of the tiny potato killing fungus 'Phythophthora

infestans" could result in the Great Famine of 1856/17 and the death of a

million people out of a population of eight and a half. But it was not solely

the loss of the potato crop which ended in death; combined with a rigid

doctrinaire attitude to famine relief and widespread absentee landlords, it was

a deadly mix.

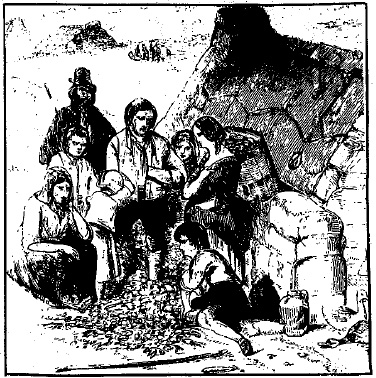

Soup Kitchens

Food for the

Government relief schemes was stored in depots but was only available at a high

price and most tenant farmers were too poor to afford it. Instead, they went to

soup kitchens, many overflowing, unable to cope with the numbers which arrived

at their doors. They died outside the doors.

Burying the dead became more and more of a problem resulting in the rapid spread

of disease. There were reports of hinged coffins and mass open graves. Today,

there are ruined workhouses all over the country and famine memorials alone

survive to remind us of those dreadful times, not even a hundred and fifty years

ago.

To paint an accurate picture of the society on which famine visited, we must

look at the report of the Devon Commission of February, 1845. This was a Royal

Commission chaired by the Earl of Devon which visited every point of Ireland as

a response to Daniel O'Connell's monster meetings which had been taking place

all over the country.

Destitute

It describes how a

peasantry had been created which was one of the most destitute in Europe. "It

would be impossible to adequately to describe," stated the Devon Commission in

its Report, "the privations which they (the Irish labourer and his family)

habitually and silently endure ... is many districts their only food is the

potato, their only beverage water ... their cabins are seldom a protection

against the weather ... a bed or a blanket is a rare luxury ... and nearly in

all their pig and a manure heap constitute their only property." The

Commissioners could not "forbear expressing our strong sense of the patient

endurance which the labouring classes have exhibited under sufferings greater,

we believe, that the people of any other country in Europe have to sustain.

Add to this the fact that before the famine, between 1779 and 1841, the

population increased dramatically by 172%, and you have a recipe for disaster.

A great part of the poverty was created by many absentee landlords who extracted

large rents out of their tenants. The Devon Commission reported that the main

cause of Irish misery was bad relations between landlord and tenant, the result

of years of rebellion and punitive legislation. Eventually, the country became

simply a source of rents which were spent elsewhere. In 1842 it was estimated

that 6 million pounds was going out of Ireland. The German traveler Kohl

commented on the mansions of absentee landlords standing "stately, silent and

empty". Absolute power was left in the hands of an agent whose worth was

measured by the amount of money he could extract.

During the eighteenth century, a system of middlemen developed when large tracts

of land were let to one person who the sub-let small amounts. Any improvement

resulted in a recent increase and so the tenant was deprived of any incentive or

security. In addition there was very little regular agricultural work for

labourers or "spailpins" because the farms were too small to employ them, except

at potato picking time. Unless a labourer could get a patch of land to grow

potatoes, he and his family would starve for thirty weeks of the year. And so

the scene was set for the famine. Then potatoes turned black overnight and were

inedible.

Even so, grain was being exported from the country throughout the period Charles

Edward Treverlyan, the Head of the Treasury, refused to restrict trade and ban

its export. Only large ports such as Cork and Belfast knew anything about

import, ports in the West being solely geared to export. And so a country

starved while its food fed other mouths that its own.

Great Hunger

People lived

exclusively on potatoes in many areas including West Cork, Kerry, Donegal and

the west of the Shannon. In those areas Government food depots were setup as

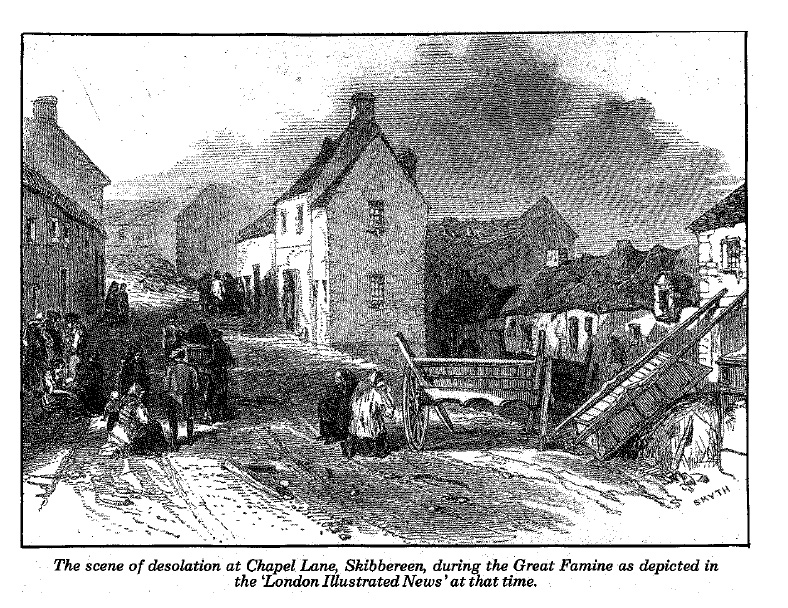

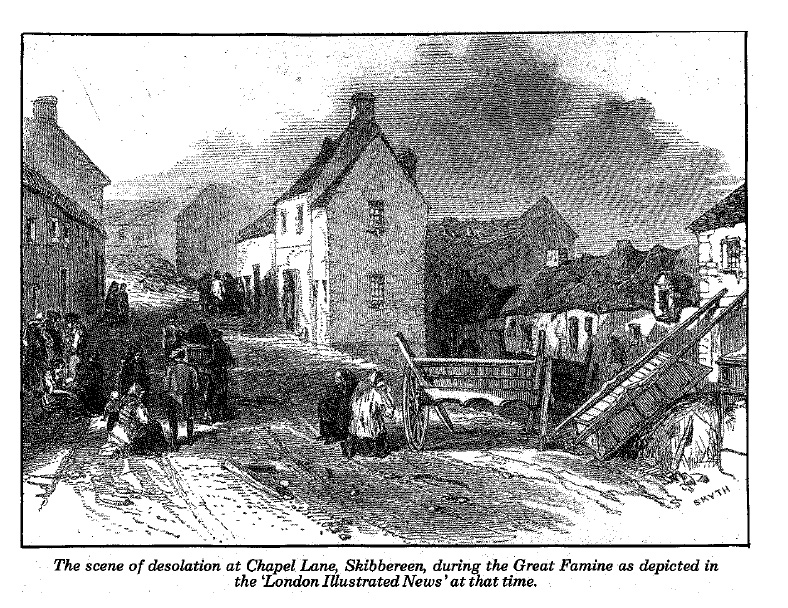

fear of famine became a possibility. In Skibbereen, it was in the charge of

Commissariat Officer, Mr. Hughes, who was answerable to Sir Randolph Routh,

Commissary General. Cecil Woodham-Smith tells the story in "The Great Hunger",

of how starvation was first reported from Skibbereen: "One market day; September

12, 1846, in Skibbereen, County Cork, an agricultural centre, there was not a

single load of bread or pound of meal to be had in the town." The Relief

Committee applied to Mr. Hughes, the Commissariat Officer, asking him to sell or

lend some meal from the Government depot. He refused, saying "his instructions

prevented him" and an angry scene followed. Two days later, members of the

Committee again came to see him, followed by a starving crowd, imploring for

food. The sight was too much for Mr. Hughes. The misery in Skibbereen, he

assured Routh on September 20, had not been exaggerated, and he issued two and a

half tons of meal, instantly distributed in small lots. Upon this, the Catholic

curate of Trellagh, a neighbouring village, came asked for two tons, telling Mr.

Hughes his people were starving and he dared not return empty-handed. Again Mr.

Hughes gave way. The curate of Trellagh was followed by the Relief Committee of

the village of Leap, who asked for ten tons. Mr. Hughes refused, and a most

painful scene took place. In the presence of Captain Dyer, the Board of Works'

inspecting officer, and Mr. Pinchen, sub-inspector of Police, the spokesman for

the Relief Committee of Leap said : "Mr. Deputy Commissary, do you refuse to

give out food to starving people who are ready to pay for it? If so, in the

event of an outbreak tonight the responsibility will be yours." What, Mr. Hughes

asked Routh, was the right course for him to pursue? Routh, in reply instructed

Mr. Hughes to "represent to applicants for Government supplies of food the

necessity for private enterprise and importation ... Towns should combine and

import from Cork or Liverpool .. Now is the time to use home produce"

By September 25 the people at Clashmore, County Waterford were living on

blackberries, and at Rathcormack County Cork, on cabbage leaves.

Serious riots took place Youghal where the sight of food being exported was

unbearable to the starving people. On 25th September, 1846 an enraged crowd

tried to hold up a boat about to sail laden with oats. Police sent for troops,

who, with difficult, stopped the crowd and Youghal Bridge. It was serious enough

for the Under Secretary at Dublin Castle, Mr. T.N. Redington, to be sent over to

London to explain to the British Government what had happened.

As autumn turned to the winter of 1846, the wild foods on which people had

existed such as nettles, blackberries and cabbage leaves began to wither and

children began to die. Fifty per cent of children admitted to the workhouses

after October, 1846 died of "diarrhoea acting on an exhausted constitution."

By November famine had reached such a point that disorganisation began to set in

. Starving mobs of men roamed the countryside like wolves hunting for food. The

employment lists for public works which should have been prepared by the local

relief committees became a farce as committee men were threatened with losing

their lives. Delays in paying wages increased the trouble.

In Clonakilty

The pay clerks in

East Carbery gave up their jobs rather than face turbulent inhabitants and at

Clonakilty the pay clerk was attacked and beaten. When a man names Denis

McKennedy died on October 24 while working on Road No. 1, in the western

division of West Carbery, at Caheragh, it was alleged he had not been paid since

October 10. A post mortem examination was carried out by Dr. Daniel Donovan and

Dr. Patrick Due, and death was pronounced to be the results of starvation. There

was no food in the stomach or in the small intestines, but in the large

intestine was a "portion of undigested raw cabbage, mixed with excrement." At

the coroner's inquest a verdict was returned that the deceased "died of

starvation caused by the gross neglect of the Board of Works." At Bandon, where

three weeks' wages were owing on October 31, deaths were alleged to have

occurred.

Charles Trevelyan, the Head of the Treasury, still maintained that enough have

been done to help Ireland and so the situation gradually became even worse. In

Skibbereen starvation have been reported at the beginning of September and

exactly three months later, two Protestant clergymen, Mr. Caulfield and Mr.

Townshend went to see him in London.

They said that the Government plans for relief were not working in their town

because the call for "practical and influential persons of property and

respectability" to help organise the relief had not been answered. No

subscription had been raised and the committee was in a state of suspension and

useless. They told him only eight pence a day was paid for working on the public

road and was not enough to feed a family. About seventy people were given soup

every day at Mr. Caulfield's house and would otherwise starve. The two clergymen

implored the Government to send food but nothing was done.

Days later, on 15th December, Trevelyan even wrote to Commissary General Routh

referring to "what is now going on in Skibbereen" and telling him not to send

Government supplies because a relief committee was not operating in the area.

"Principles must be kept in view," he wrote. Nobody questioned what principals.